Animal studies have provided strong evidence that gut bacteria play a role in neurodevelopment. More specifically, altering intestinal microbiota has been found to impact cognitive, communicative, and exploratory behaviors. Very few human studies have been conducted on the relationship between different types of gut microbiome colonisation and brain development, until now.

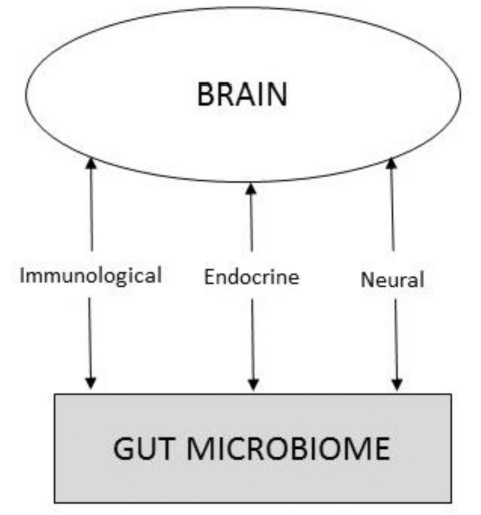

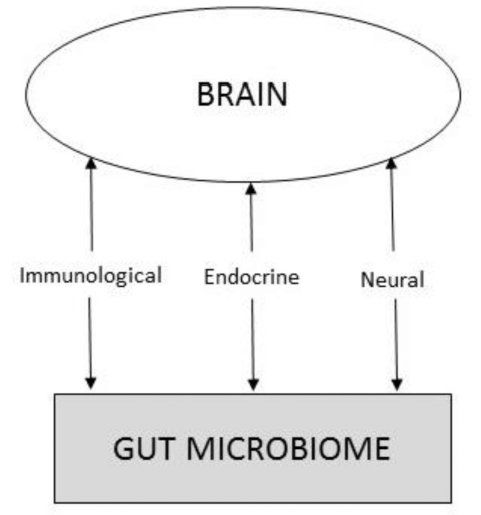

Recent studies into gut bacteria are uncovering new and unsuspected roles for how they interact with the rest of the body. There is evidence that gut bacteria can protect or predispose us to pathologies ranging from inflammation to diabetes and obesity. There is more recent research showing that gut bacteria can modify our mood and behaviour.

Factors known to affect the composition of the infant microbiome during the birth process and the first 1,000 days of life include: the mode of delivery (vaginal or surgical), antibiotic exposure, and infant feeding patterns. New evidence is also showing the influence of maternal stress and other factors on the composition of the infant microbiome as well.

But what role do our gut bacteria or microbiome have in neurological development?

A human study on gut-brain-microbiota interactions from research teams at UNC School of Medicine and the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) was published recently that adds to the importance of a healthy infant microbiome for neurological development.

In results published in Biological Psychiatry, faecal samples were collected from one-year-olds and cognitive assessments of the same children were done one year later. The research identified an association between certain kinds of microbial communities in the gut and higher levels of cognitive development later on.

The faecal samples collected from 89 typically developing one-year-olds were analyzed and clustered into three different groups, based on similarities in their microbial communities.

At age 2, the cognitive performance of these children was assessed in a series of tests that examine fine and gross motor skills, perceptual abilities, and language development. Infants in the cluster with relatively high levels of the bacterial genus Bacteroides had better gross motor skills, perceptual abilities, and language development, compared to the other two clusters.

Interestingly, babies with highly diverse gut microbiomes didn’t perform as well as those with less diverse microbiomes. The result was surprising as other studies have shown that low diversity in infancy is associated with negative health outcomes, including type 1 diabetes and asthma. This work suggests that an ‘optimal’ microbiome for cognitive and psychiatric outcomes may be quite different than an ‘optimal’ microbiome for other outcomes in life.

How these bacteria are influencing the gut is still speculative. However, what is emerging is that the gut microbiome, even at the age of one, there is the beginning of adult-like gut microbiome communities. Which means that the ideal time for intervention would be before age 1. Further investigation has been suggested, including relating the infant gut microbiome to other aspects of child development, including the emergence of social skills and anxiety.

These results suggest you may be able to guide the development of the microbiome to optimize cognitive development or reduce the risk for disorders like autism which can include problems with cognition and language. However, any intervention would have to start early.