Poor sleep in autism is finally becoming recognised as a major issue and a central feature of autism. Up till now other issues like speech, behaviour or epilepsy have been a priority.

I have already written about sleep issues in ASD previously. More recently there is more interest in treating poor sleep in ASD and ADHD as a primary objective.

Parent surveys suggest that over 80% of ASD children may struggle to fall asleep or stay asleep. Problems with sleep varies from child to child, but the consequences of poor sleep are universal. Parents and caregivers have heightened levels of stress. For the child sleep problems just exacerbate many of the challenging behaviors associated with autism. These may include hyperactivity, compulsions and rituals, poor attention and aggression.

Bedtime resistance and nighttime wakefulness appears to have the strongest association with aggression and features of ADHD like inattentiveness and impulsiveness. Sleep disturbance has also been associated with anxiety, suggesting a relationship between poor sleep and mood. One study found that sleep problems in children with autism are among the strongest predictors of hospitalization.

With such a strong association between poor sleep and daily functioning, it is surprising that only about 30% of parents report that their child’s sleep issues have been addressed.

There is a lack of research on autism and sleep. A PubMed search reveals nine clinical trials on autism and sleep in the last 5 years, compared to over 400 clinical trials of treatments for core autism traits over that same period.

Part of the problem is how do you study sleep problems in ASD. Polysomnography (tracks a person’s brain waves, eye and limb movement, and breathing patterns during sleep) is difficult to do on ASD children as it requires children to spend a night or two in a sleep laboratory with a variety of sensors on their head and chest. Those that can tolerate it may be on the milder end of the spectrum, which can skew the validity of the results.

Interestedly, more studies over the past few years suggest that sleep issues may stem from some of the gene mutations that underlie some of the characteristic features of autism. A 2015 study suggests that individuals with ASD are twice as likely as typical people to have mutations in genes that govern the sleep-wake cycle. Some studies suggest that ASD individuals carry mutations that affect their levels of melatonin, the natural hormone that controls sleep.

Electronic Gadgets

Children seem to be drawn to electronic devices. Exposure to the light emitted from these devices can make it harder to fall asleep, and if they wake up, harder to fall back to sleep. When teenagers can’t sleep, they may turn to these devices to pass the time. I have had one mother say that their child was waking up at night and playing on an old mobile phone during the night and falling asleep during the day. It was a mystery as to why he was so tired and sleepy until the phone was discovered in his room.

Sleep in people with ASD may also be less restorative than it is for people in the general population. They spend about 15 percent of their sleeping time in the rapid eye movement (REM) stage, which is critical for learning and retaining memories. Most neurotypical people, by contrast, spend about 23 percent of their nightly rest in REM.

How to address sleep in ASD?

The first step is to deal with any medical issues like sleep apnea, seizures or gastrointestinal problems (faecal impaction, abdominal pain). Abdominal cramping or discomfort may keep them from falling asleep or wake them at night. Hunger or low blood sugar levels at night will increase cortisol and the child fully wakes and just wants to play. ADHD or anxiety may disrupt sleep. Prescribed medications may affect sleep. Stimulant medications for ADHD may cause insomnia. Antipsychotic medications can cause daytime sleepiness that can affect the quality of nighttime rest.

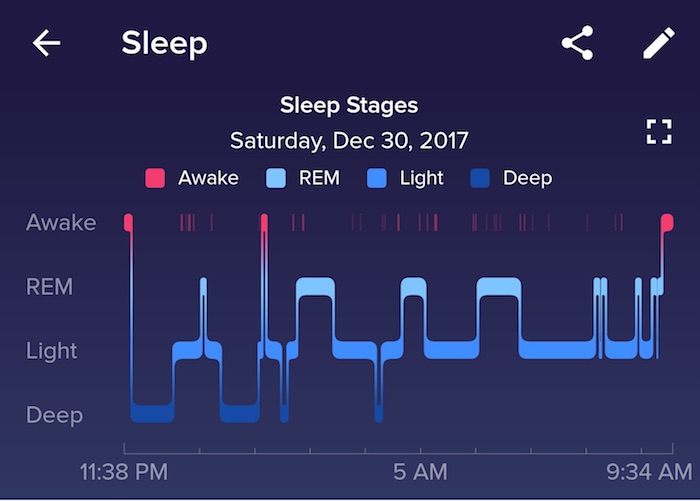

Sleep quality can be assessed by actigraphy, in which a watch-like device (eg. Fitbit tracker) on the wrist records a person’s movements throughout the night. This is usually well tolerated by a child. Indeed, I have had a number of mothers come into the clinic and shown me the nightly graphs of the quality their children’s sleep. It tracks how long they are in a deep sleep and when they are moving or awake. It is surprising how little these children are in that deep sleep phase at night.

Encourage more activity in the child’s routine, increased activity during the day and less stimulation at night can be very beneficial.

Some research points to evidence of that ASD children tend to be in a heightened state of arousal, or in “fight or flight” mode. Many have sensory or gastrointestinal sensitivities, elevated levels of anxiety, and some studies suggest that they have faster heart rates while awake and while sleeping. This hyperarousal can be a contributor to poor sleep. Anything we can do to decrease anxiety and hyperarousal will be beneficial. Some options to consider have been covered previously in Sleep Issues in ASD.

Melatonin has been particularly useful for ASD children. One study found that melatonin was 63% effective for children that used it. It was particularly effective when used in conjunction with behavioural modification. Although melatonin is considered safe there are a few issues. Melatonin prescribed by a doctor and dispensed by a pharmacy has been manufactured to pharmaceutical standards. However, many parents buy melatonin online from overseas. The problem here is that because melatonin is considered a supplement rather than a drug, regulatory authorities like the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) do not regulate the quality of the supplements that contain melatonin. A study published in 2017, analyzed 31 such supplements and found that two out of three did not match the dosage on their labels. Some brands contained less than one-fifth of the advertised dose, and others contained four times more. Some also contained the neurotransmitter serotonin, which is a controlled substance and is toxic at high doses. If using melatonin, more does not mean better results, as some children actually do better on lower doses rather higher doses of melatonin. Therefore, always start at a lower dose initially.

In November 2017, researchers published results from a clinical trial of 125 children with autism for a new melatonin product, called PedPRM. The small tablets release melatonin slowly into the bloodstream and represent the first melatonin formulation developed by a pharmaceutical company. The tablet is small, only 3mm in size, and contains a precise dose of melatonin and is easy for children to swallow. While a dose of melatonin may help someone fall asleep more quickly, it may not keep them asleep. This is a slow release formulation that mimics the way melatonin is secreted in the body and more likely to help the child stay asleep throughout the night. After 13 weeks of treatment, children who took the tablet slept, on average, an hour longer than they used to. They also fell asleep an average of about 40 minutes faster.

The company hopes to make the drug available by prescription in Europe by October 2018 and is aiming for U.S. approval after that. Hopefully it will also become available in Australia very soon also.